Weekly Update - April 18, 2025

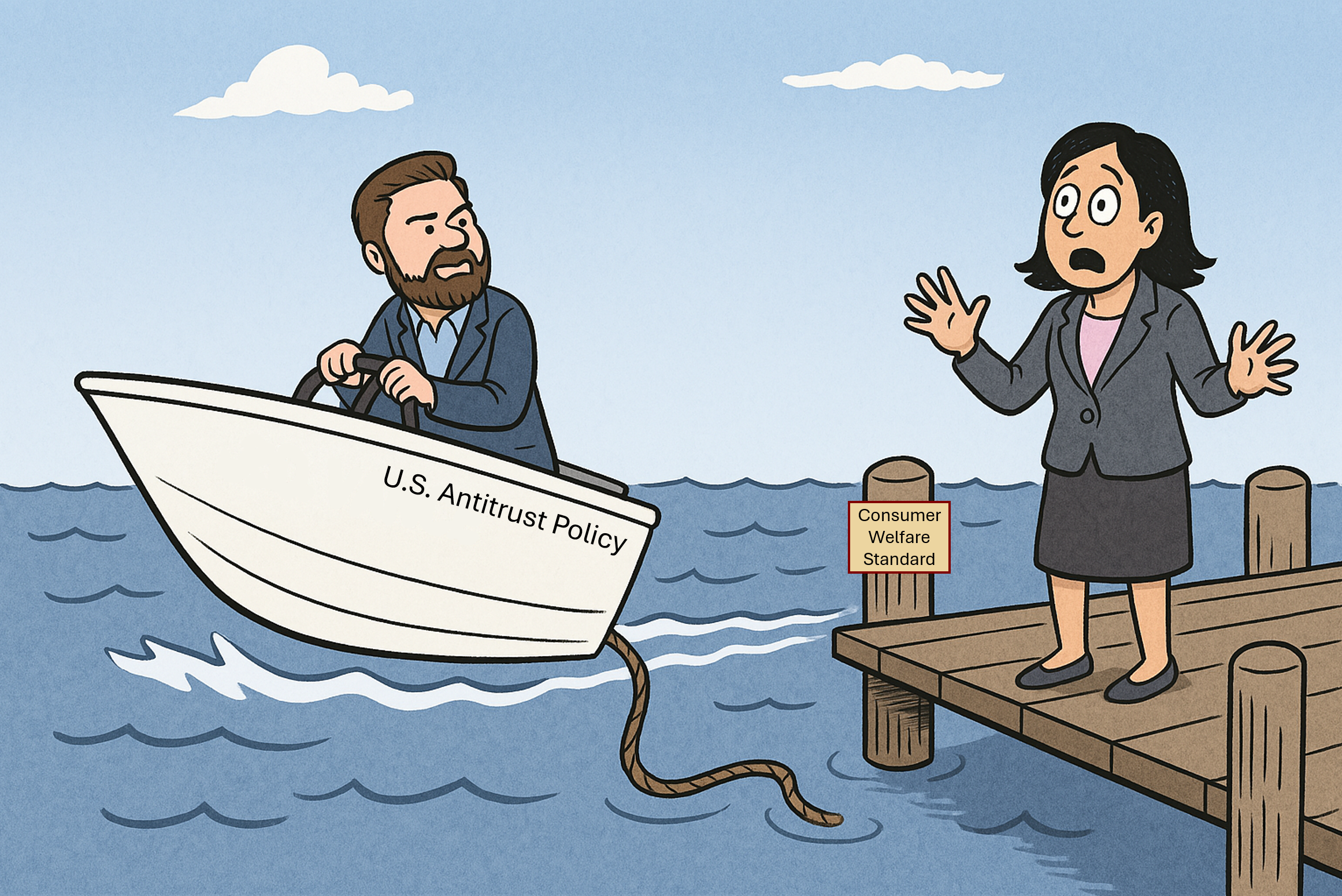

An illustration for this Axios article. Lina Khan has unmoored antitrust enforcement from the consumer welfare standard, and now J.D. Vance is using it for his ends, to the dismay of the neo-Brandeisians.

Last Week's Posts

Popular Posts

Tariff Calculus

An explanation of how Trump's team determined the tariff rates and what they got wrong

Other Interesting Reads

What Happened To Never-Needed Regulations

Ryan Young CEI

The Census Defines the Poverty Rate Up

Phil Gramm; John Early WSJ

Another Wrong Way to Measure Poverty

Phil Gramm; John Early WSJ

The 3 Myths Supporting NIH Funding

Zachary R. Caverley Reason

Thanks to De Minimis Exemption, Forever 21 Won't Be Last Bankruptcy

Wilmer Leon RealClearMarkets

Reconciling the Official Poverty Measure and CBO’s Distributional Analysis of Household Income

CBO CBO

A Win-Win Proposal to Fix Social Security

Tyler Watts EconLog

Argentina's DOGE

Alex Tabarrok Marginal Revolution

Don't let the next crisis grow the government—again

Clyde Wayne Crews CEI

Reflection after Five Papers about Climate Change

David Barker Econ Journal Watch

How Liberty Upsets Patterns

David Henderson EconLib

Why We Cannot Have Nice Things

Scott Sumner EconLib

Eisenhower Warned Us About the Scientific Elite

Zach Weissmueller Reason

Computational Analysis of US Congressional Speeches Reveals A Shift from Evidence to Intuition

Various Nature

Regulatory quality is declining

James Broughel Mercatus Center

How do you ask good questions

Tyler Cowen Marginal Revolution

High US health care spending is quite well explained by its high material standard of living

Unknown Random Critical Analysis

New Montana Law Blocks the State From Buying Private Data To Skirt the Fourth Amendment

Joe Lancaster Reason

Selected X Posts

From Others

This is a poor joke, but my son and I have challenged each other to write original knock knock jokes.

— David Marcus (@BlueBoxDave) April 11, 2025

His was masterpiece was:

Knock knock

Who’s there?

Kamala Harris

Kamala Harris who?

I’m sorry, I’m not taking questions at this time.

It’s really good. https://t.co/98Ukm7oDxf

— Sal the Agorist (@SallyMayweather) April 4, 2025