I cannot recommend more highly this Ross Douthat Interview of Oren Cass. Douthat treats Cass as a serious thinker and with respect. He asks excellent questions and gets thoughtful answers that help characterize Cass's views.

I don't agree with Cass on very much regarding trade, and his style of speaking is nebulous and difficult to parse for succinct arguments. Also, on Twitter, he's more aggressive and personal than I prefer, but it's still worth taking his point of view seriously.

In this interview, a few main throughlines emerge. Unlike the MAGA protectionists, Cass is dubious of some of the arguments regarding tariffs, though he's careful to not dismiss them outright. For example, he's not really sold on the abrupt Trump approach but thinks tariffs need to occur more gradually.

Below are the fundamentals of the Cass trade system.

- The 2025 American economy, despite the commonly used metrics, is not working.

- Income, unemployment, and GDP do not account for the high prices Americans pay for fundamental material necessities of life like education, homes, cars, healthcare.

- Economic metrics exclude non-economic aspects of life—family, security, etc.— which have diminished the past 50 years.

- Not all groups are keeping up. Young men, particularly in the rust belt, are falling behind.

- The national security rationale - We need to build defense products domestically.

For these reasons, he supports a broad tariff; he's happy with the across-the-board 10% tariff Trump imposed. He supports a much higher tariff on China because they're a hostile state but also is open to freer trade with friendly countries as long as they (1) adhere to the larger goal of isolating China and (2) have "balanced" trade restrictions with the U.S.

Where I disagree

First, even though I'm an economist, I'm not going to say that everything is better for everyone in the U.S. today compared to 1975. It's true that life is a lot cheaper overall, and the standard of living is a lot higher for the vast majority of Americans. I don't think there are many people who would choose to live in 1975 over 2025.

That being said, I agree with him that men in the rust belt who are not college-educated, as a demographic group, have probably done the worst in the past 50 years as the economy evolved. Despite that, I don't believe the solution to the relatively slow growth for one group of people to hold the rest of the country back.

The left often solves these problems by redistributing wealth; the right's solution used to be laissez faire, and letting them work themselves out; Cass represents a new right, though, and he wants to redistribute opportunity instead of wealth. By imposing tariffs and trade restrictions, he wants to promote domestic manufacturing jobs at the expense of trade-based jobs. This will cause an enormous amount of harm—much greater than the gain to this one demographic group.

It's a challenging problem to solve because it involves several frictions in the choices of individuals. Individuals might need to retrain, switch industries entirely, relocate. All of these are very difficult, and especially so if the economic changes are abrupt. Up until 2020, more and more men were getting college degrees, which helps solve the problem, and incomes for high-school graduates did rebound since 2015 after declining over the previous decades.

Still, the solution to this problem is not to hold back or reverse the gains the country has made. A huge proportion of America has gained from having the most dynamic economy in the world, and winding the clock back 50 years to a time where there was more manufacturing, for a single American demographic will surely do more harm than good.

In addition to that, there's no reason to believe that Cass's system will benefit the people he's worried about disproportionately. Later in the interview, he argues that he views the 10% broad tariff as a free market solution, meaning that the U.S. economy will figure out the best way to achieve his goal of reshoring production. This will mean we pay more for certain goods, but we also produce more of other goods, in whatever configuration that is most economical/profitable.

Why does he believe that the final configuration will mean more jobs for 25-45 year old, high-school educated men in the rust belt? There's every reason to believe that production will favor the South where people have been moving and have more attractive environments for business investments. There's no reason to believe that the jobs that are created won't favor the same types of people who are already doing well.

Prices of the Fundamental Goods Won't Go Down

At American Compass, we look at the cost of attaining the sort of basics of middle-class security, like health insurance, housing, transportation, the ability to send your kids to public university, a basic basket of food. Now, that frustrates economists because that’s not the standard inflation measure, but those costs resonate with a lot of people because it speaks to the reality of their lives. It has become much harder for the typical worker to afford all of that, especially on one income."

Firstly, I am in no way frustrated by choosing these goods. I think there's merit to it, even if it does neglect many goods that people like to buy. There's much more detail at American Compass's website.

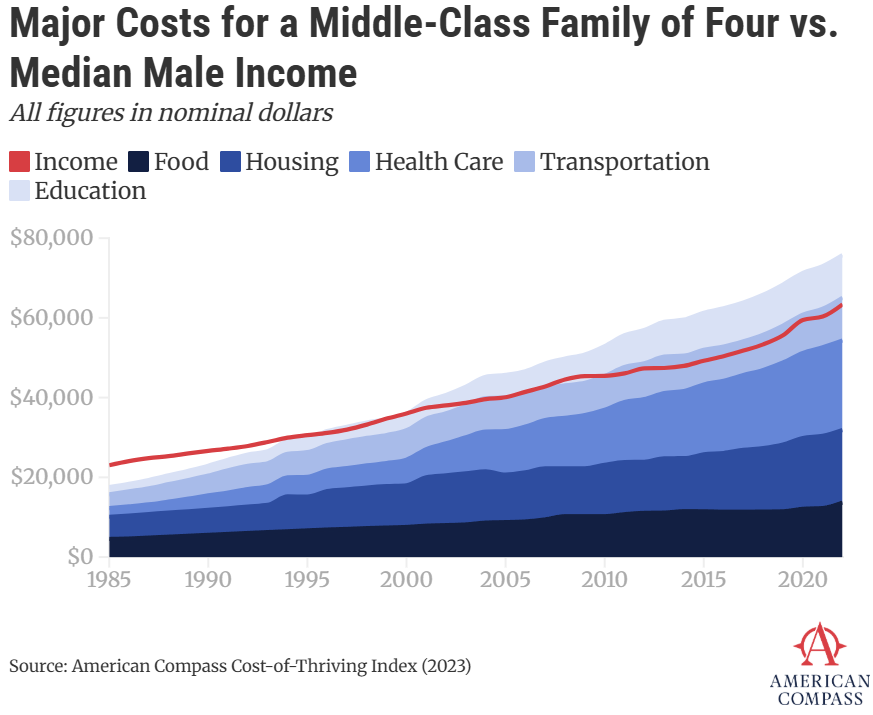

This graphic does a pretty good job illustrating his point. The red line represents income, and the other lines are the combined costs of Food, Housing, Health Care, Transportation, and Education. Notice how in 1985, a single median male could afford all of these items for his family of four, and that is no longer the case in 2022.

However, one should note a few things. The difference isn't all that large. In 1985, the earner is barely able to afford these things, and by the end, he's barely unable to afford them. Secondly, the categories that increased the most were Housing, Health Care, and Education. The others stayed proportional for the most part. Health Care is double-counted, too. In the index, they use the full premium, which is partially paid by the employer. If you do this, that part of the premium should also be included in the weekly income.

Education and Housing both go up, but largely because these items are paid for by dual-earning households coupled with the limited growth in the supply of these products. The better solution for both of these is to work toward greater supply.

Lastly, like with the previous criticism, it's unclear if or how tariffs will fix these problems. Tariffs will not lead to fewer dual earners, more universities, or more homes. They'll probably make housing more expensive, in fact, as well as transportation, food, and health care. Will wages go up for the one slice of the population that has fallen behind? If so, is the plan essentially to limit the success of the couples, so they won't bid up prices of the same products that the single-earner wants to buy for his family.

The National Security Argument

National security is one of the better reasons advocates give for protective tariffs. In the event of a war, we want to make sure we can produce all the weaponry and equipment we will need to win. To me, though, while this makes sense in the abstract, there are a hundred issues and possibilities that need to be considered. Would it be acceptable to divide up wartime essentials among our closest allies or can we not trust them either? The United States has transitioned its economy at the outset of a war several times in the past and still won those wars; surely for some products we can just be prepared without actually producing those items during peace time.

What Cass is actually proposing becomes somewhat hazy here. Douthat asks if, for national security, we should just focus on a couple highly important products like chips. Cass says "If you actually want to be an industrial power, you need the actual materials themselves. You need to know how to make the tools that make the materials, things like machine tooling, the actual excellence in engineering that’s going to lead to efficient production." He then says he thinks of tariffs as a free market solution, so it's extremely unclear how he wants to effect the national security component

Cass seems simultaneously opposed to using tariffs to single out certain products, but also implies that America needs to produce national security goods at every point of the process, from nuts and bolts to finished missiles. Beyond the internal contradiction, producing every screw, bolt, panel, etc, etc, etc, for our incomprehensibly sophisticated Air Force jets, nuclear submarines, and intercontinental ballistic missiles would require committing a tremendous percentage of the nation's economy to achieve, if it was achievable at all, considering some of the raw materials may not be available in the U.S.

Conclusion

Oren Cass has a mostly coherent, and much more focused vision of trade and what it should achieve than most of his allies on the issue. Still, it is not fully fleshed out and leaves many important questions unanswered. I retain my view that he's more wrong than right, but at least I understand him better because of this interview.

Some Interesting Excerpts and Selected Reactions

But when we're looking at the actual well-being and flourishing of the typical working family and their ability to achieve middle-class security, we've seen real decay.

Cass believes the current economy looks very good, but it's a temporary bright spot on a downward slope.

When you’re looking at these household income numbers, it’s important to notice how much they rely upon the household having two earners and how much more reliant they find themselves on government programs than in the past. I also think it’s important to notice rising inequality, which conservatives have traditionally pooh-poohed in the last 40 years. That’s because you’re not supposed to have any right to complain about the broader shape of the society as long as you have more stuff than you did 40 years ago. But I think we’ve seen a very clear divergence in the fortunes of the typical worker, who does not have a college degree, and the upper middle class, who has seen so much of the benefit.

At American Compass, we look at the cost of attaining the sort of basics of middle-class security, like health insurance, housing, transportation, the ability to send your kids to public university, a basic basket of food. Now, that frustrates economists because that’s not the standard inflation measure, but those costs resonate with a lot of people because it speaks to the reality of their lives. It has become much harder for the typical worker to afford all of that, especially on one income.

...What people are seeing instead is that some people got to march ahead into the brave new future and a lot of folks did not. This may be somewhat narrow, but I think it’s really important to look at particular groups, like young men, if you want to know how your society is doing."

Cass here is saying a couple different things. First, that the measures of economic prosperity are misleading because they're based on dual incomes and government transfers. Also, he highlights income inequality, which was once the primary preoccupation of the left. It was a very big issue in the mid-2000s for Democrats. Books were written on it. This was true when the Bush II economy was doing remarkably well before the financial crisis.

To this, Douthat asks the very reasonable and natural question, what trade has to do with this.

Cass responds:

What we have seen going back into the ’90s after NAFTA, and certainly after welcoming China to the World Trade Organization, is a real hollowing out of the manufacturing sector.

The loss of manufacturing has been a serious problem, and trade is at the heart of that. So, figuring out how to make it relatively more attractive to make things here in America is therefore becoming a really big — and correct — focus for policymakers.

A flatlining in the manufacturing sector is a form of collapse that weakens the American ability to essentially keep up in all sorts of vital areas.

Seemingly contradicting himself, Cass says:

I think it's important to say that there's nothing especially valuable in the abstract about a manufacturing job

But this goes back to underscore the main reason he cares about manufacturing in the opening of this post: 1) the people who used to have manufacturing jobs have been left behind and these jobs are the best way Cass sees to reinvigorate them and 2) national security.

...one thing that is very good about manufacturing jobs is where they tend to be located. If we want a broad prosperity with diffusion across the country, then it’s important to have strength in a variety of sectors in different places, not just knowledge work that’s going to agglomerate in a few big cities.

It’s also the case that if you want to have good, highly productive jobs that pay a good wage, empirically, what you see is that those opportunities exist in the manufacturing sector, especially for people with less formal education, even though the average manufacturing job doesn’t pay more than the average services job.

Short-term vs long-term

The funny thing is that when we have talked about short-run costs of globalization, economists just waved them away and said, Oh, don’t worry. Let us tell you about our long-run equilibrium model that says, you know, someday this will be for the best.

It’s only when you’re talking about policies that are not their ideological preference that they suddenly zoom in and focus very heavily on the immediate short-run transition costs. So I certainly acknowledge there are short-run costs, but I think they’re worth it.

I don't think this is true at all. Economists do tend to talk about the long-term costs, but they talk about short-term costs as well. And in this case, economists worry about both the short- and long-term costs of tariffs.

Not only because of the other things beyond G.D.P. that we might accomplish, but I think they’re also worth it because they point in the direction of a much stronger and healthier economy in the long run. And so we’re looking at what trajectory is the right one for the American economy across the next generation or two.

I absolutely think that we’ll be much better off if we make a commitment to reindustrialization rather than saying, Well, according to the economic model, we should just be happy with everything being produced in China because it’s more efficient there and we get cheaper stuff."

Cass truly believes in the long-term benefits of tariffs.

National Defense

I think it’s really important to recognize that you can’t maintain a strong defense industrial base independent of a strong industrial base. We’ve essentially tried to do that. We’ve said we still need to be able to make our own aircraft carriers and submarines and fighter jets and so forth. But the other stuff doesn’t matter because it’s not national security.

If you actually want to be an industrial power, you need the actual materials themselves. You need to know how to make the tools that make the materials, things like machine tooling, the actual excellence in engineering that’s going to lead to efficient production.

Here, he's saying that the U.S. needs to produce all elements of the national security products, from nuts and bolts to finished missile.

Tariffs as a Nudge

I always emphasize that I actually see tariffs as the much more free-market position. Because, yes, they are a significant intervention into the market, but they are a relatively simple, broad and blunt one. And once you’ve changed the constraints such that domestic production is relatively more attractive, you then are able to leave more to the market to figure out. Under these conditions, what else do we want to produce here? And how do we do that effectively?

Cass sees tariffs as a sort of carbon tax or cap and trade. A single price to orient the entire market, but let the market figure out how best to do that. I don't think this works. On a carbon tax, for example, you set the price to target a specific level of carbon, and then you let factories decide who pollutes more and who pollutes less, but the total is set. With industrial policy, there is no specific target. Cass's goals are to lift up a single demographic category and reshore defense production. Neither of these things is best accomplished through a broad tariff, unlike a carbon tax.

I think the most constructive agreements we’re likely to reach are around pushing toward balanced trade and around pushing toward getting China out of our markets. I think we can make a lot of progress there. I don’t think we’re going to solve our deficit problems through those negotiations.