People are pointing to a publication written by Trump's Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers Stephen Miran back in November 2024 as a blueprint for what Trump is doing right now, and how he views trade. While Trump has digressed substantially from that blueprint, and Miran himself has avowed that his approach does not reflect the administration's policy the argument Miran makes is a pretty interesting one, and worth understanding better. Also, it's worth evaluating the evidence behind some of the claims he makes.

The best insight from this paper is that the use of the U.S. Dollar as a reserve currency by the rest of the world causes trade deficits with the U.S. to be larger than otherwise. Basically, the other countries receive U.S. dollars and then have to choose to spend it on U.S. goods, invest in U.S. companies, exchange it for their own currency, or use it as a reserve currency the way gold was used prior to the modern financial system. If they choose the last option, then it distorts the markets for goods and trade balances. The more dollars they devote to the reserve function, the more trade balances will be distorted in favor of the U.S.'s trading partners.

He then argues that a big reason the U.S. carries trade deficits with so many other countries is because these countries are deliberately, and against their own economic interest, devoting much of the American money toward the reserve function. Finally, Miran suggests that we should reduce the trade deficits by using tariffs but also by disincentivizing the foreign purchase of U.S. debt, and offers several ways to accomplish this.

However, in spite of this one insight, Miran makes several arguments or statements that are incorrect:

- His argument requires that our trade partners must be increasing their holdings of U.S. debt.

- He claims that foreign countries are driving our high debt levels.

- He assumes that foreign purchase of our debt provides no benefit to Americans.

- He argues that without the debt factor, foreigners would bear the full burden of U.S. tariffs.

- He argues that without the debt factor, tariffs would impose minimal effects on trade flows overall.

All of these contentions are wrong, even in his hypothetical world of perfect currency adjustment. Below, I lay out why in more detail.

U.S. Debt Statistics Don't Support Miran's Argument

As mentioned in the intro, when exchanges of goods take place between countries, just like when two people are exchanging goods, they use money to facilitate the process. For a foreign country, though, when they receive U.S. dollars in exchange for their goods, they have to return them to the U.S. somehow because their economies use a different currency.

There are a limited number of ways they can return the dollars to the U.S.:

- Purchase American goods

- Exchange the U.S. currency for their own through a currency exchange

- Invest in American production (e.g. building a BMW plant in South Carolina or purchasing stock in Apple)

- Invest in American debt (U.S. Treasury Bonds)

Much of Miran's case rests on the fourth use—investing in American debt. This is how countries, in practice, employ the American dollar as a reserve currency. His argument is that the first three are productive and natural uses and lead to a free-market equilibrium state where trade balances correctly, but the fourth distorts that equilibrium. Further, other countries understand this effect and take advantage of it to distort trade deliberately and favor their own production.

An element of Miran's argument is that by virtue of being the reserve currency, there's a set amount of U.S. dollars that need to float around the world economy, and in fact, that set amount has to go up as the world economy grows. But if the world economy grows faster than the U.S., which it has recently, then the foreign countries will need more U.S. currency, in the form of U.S. Treasuries, to support the system. This will lead to higher demand for U.S. Treasuries, a stronger U.S. dollar, and larger trade deficits with the U.S.1

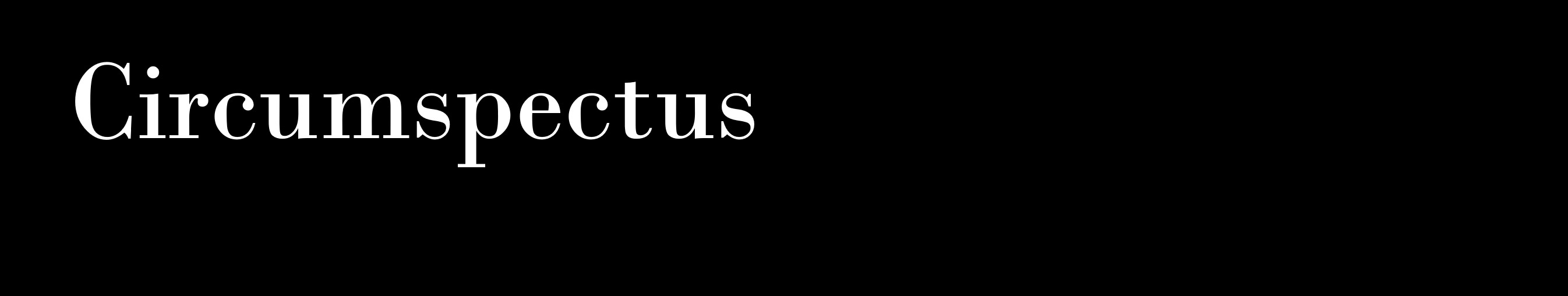

While this is all true in theory, in practice it doesn't seem to be the case. Whether the other countries are deliberately distorting trade balances by buying up U.S. Treasuries or if they're just retaining a certain store of dollar-denominated debt to maintain their reserves, you'd expect the amount of debt they hold to go up not just in absolute amount, but in proportion to the world economy.

The chart below shows this isn't the case. Miran's claiming that the reserve status of the dollar will mean foreign countries will have to increase their reserves in proportion to the growing world economy, and this will become a larger and larger proportion of the U.S. economy. Neither of these contentions are true. Holdings of U.S. debt are falling as a percentage of the world economy and the U.S. economy and have been doing so for ten years.

Foreigners' U.S. Debt Holdings as Percentage of Economy

Sources: U.S. Debt Information (U.S. Treasury), U.S. GDP (FRED), World GDP (Our World in Data). World GDP was adjusted to be nominal (to match U.S. GDP and Treasury Data) using PCE price index.

Miran Gets Cause and Effect Wrong on U.S. Debt

"America runs large current account deficits not because it imports too much, but it imports too much because it must export U.S. Treasuries to provide reserve assets and facilitate global growth."

Miran here is claiming that because other countries use the dollar as the reserve currency, it forces America to issue more debt to satisfy the demand. That is the reverse of the truth. The U.S. issues debt because it spends more than it collects in revenues. The United States spent $6.75 trillion dollars in 2024. That's $6,750,000,000,000. It spends this much because Congress is insensitive to debt, and voters want more spending on all things. Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid get larger every year and no one wants to cut them so Congress keeps spending. This is true of nearly all government programs.

And while the government is spending $6.75 trillion, it only collects $4.92 trillion in revenues. This is because no one wants to pay higher taxes. To make the math work, we have to get the money from somewhere, so the government sells Treasury bonds to make up the difference every year. Some of those bonds are sold to foreigners and foreign countries, yes, because of the reserve currency issue, but it is an error to believe that the latter is causing the American voters to spend more than they pay on government services and transfers.

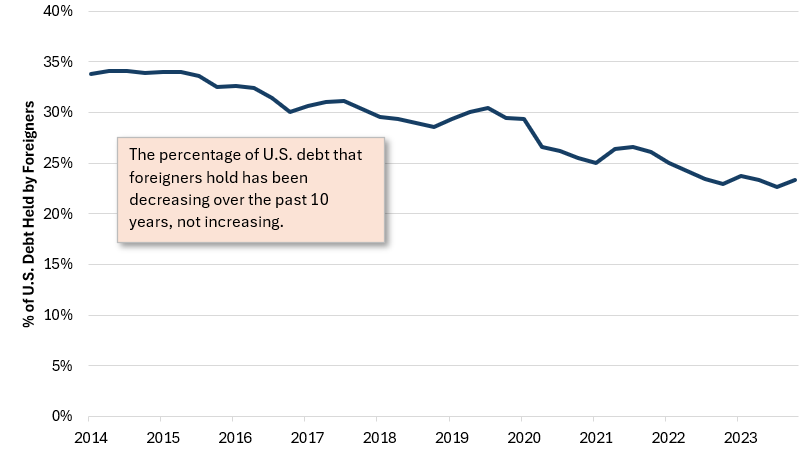

Percentage of U.S. Debt Held by Foreigners Over Time

Source: U.S. Treasury

The chart above shows that foreigners, while they're buying more debt every year, they're slowing down, and the percentage of U.S. debt they own has been falling. This demonstrates that they are clearly not driving the U.S. debt levels higher at all. At the end of 2023, foreign countries held less than 1 out of every 4 dollars of debt, and that ratio was shrinking.

What these foreign countries are doing is actually subsidizing our debt. Because they want to buy the bonds, it increases the demand for the bonds, which means the Federal Reserve can sell bonds with lower interest rates. If foreign countries weren't using the dollar as a reserve currency, the interest on our national debt would be even higher than it is. Essentially, because the dollar is a reserve currency, it allows us to pay less for generous Social Security and Medicare benefits. Would we have as much debt if foreign countries bought less? Possibly. To date, the American public and government have not been sensitive to the increasingly high interest we paid on our debt. At some point, that will probably change, but foreign purchases are not making a material difference in that right now.

Foreign Purchase of U.S. Debt is not Necessarily a Bad Thing

Miran also suggests that foreign countries are purchasing U.S. debt, not because it's in their economic best interest, but as a protectionist tactic to favor their own country's producers. As mentioned before, by purchasing U.S. Treasuries, other countries avoid buying U.S. goods or exchanging their own currency and, as a consequence, increase trade deficits between the countries. This is a significant part of the problem that he wants to address and suggests ways to make foreign purchase of debt more costly.

Again, though, the problem here is that the U.S. has so much debt to sell. If the U.S. balanced its budget, it wouldn't need to sell as many bonds, and the interest rates would go down, so countries would be disadvantaging themselves even further by purchasing bonds instead of using the money for more productive endeavors. Countries would have a stronger disincentive to purchase our debt to manipulate trade if our deficits were under control and U.S. debt had lower interest.

Also, instead of thinking of this as these countries cheating to benefit themselves, it's more accurate to think of it as them harming themselves. They are essentially paying Americans to help the special interests in their own country. These countries are deliberately choosing to lose money so that their producers can benefit, but overall they're worse off. By contrast, United States is better off overall because the foreign countries are effectively giving us free money that we can spend as we choose.

Foreigners Do Not Bear the Full Burden of Tariffs

"In a world of perfect currency offset, the effective price of imported goods doesn’t change, but since the exporter’s currency weakens, its real wealth and purchasing power decline. American consumers’ purchasing power isn’t affected, since the tariff and the currency move cancel each other out, but since the exporters’ citizens became poorer as a result of the currency move, the exporting nation “pays for” or bears the burden of the tax, while the U.S. Treasury collects the revenue."

Anyone who reads this, and especially economists who read this, should immediately be skeptical. One of the most widely known economic mantras is "There is no such thing as a free lunch," yet this paragraph purports that there is. That the U.S. can raise a tax rate and Americans will not have to pay one penny, and it will be harmless to them in the end.

Miran reaches this conclusion by adding foreign currency and currency exchanges to the equation, and then assuming that the currency exchange will offset the tariff. He argues that if the U.S. imposes a tariff, that will lead to fewer dollars floating in the world, which will raise the value of the dollar and reduce the value of the foreign currency. This part is true. He then purports that the reduction in the foreign currency will completely offset the tariff. But there is no reason to believe that's true and many reasons to believe it isn't.2

To see this, imagine a world that has no currencies at all, so all trade is done via barter for goods. If the U.S. sells Colombia wheat in exchange for coffee, just like if the exchange was between two people, the value of the wheat has to basically match the value of the coffee. The U.S. will not send over the entire wheat supply in exchange for one K-cup of coffee, but there will be some balance based on individual preferences and all kinds of other factors.

If the U.S. imposes a 10% tariff on the coffee, then the Americans have to give the government 10% of the wheat they trade or 10% of the coffee they receive, or some combination that adds up to 10%. Who's worse off? Undoubtedly the Americans are worse off. They have two opposite choices: give the government 10%3 of their wheat and trade the remaining 90% for coffee, in which case they can only get 90% of the coffee as pre-tariff. Or trade all of their wheat, and then give the government 10% of the coffee. They still end up with 10% less coffee. The foreigners end up with either 10% of their coffee supply remaining after the trade in the first situation, or all of the wheat, in the second, so the cost to them is minimal.

When you add currency into the equation, if it's perfectly exchanged as Miran assumes, that fundamental outcome cannot and will not change. It would violate logic if adding a medium of exchange like dollars to a trade fundamentally changed the outcomes of a policy. The existence of a currency that facilitates trade does not change the underlying preferences and values of consumers with respect to goods.

Adding more currencies, more goods, and more countries will not change the outcome and does not leave the foreign country footing the entire bill of the tariffs as Miran postulates.

Trade Flows Will Be Affected, Especially Exports

Miran claims that raising tariffs will have little effect on trade flows. Miran clearly knows that this isn't true. This is the one absolute result without counter-effects of the tariff, even in his hypothetical world of perfect exchange rates. The tariffs will first cause imports to decline, because the price goes up. If imports decline, fewer U.S. dollars go out into the world and countries have less cash to buy American goods, so it's likely that U.S. exports decline as well. For imports, though, some of the reduction will be offset by the revaluations of currency. The foreign currency will go down and the American currency will go up. This change means U.S. imports go back up because they're cheaper to Americans, but U.S. exports go down, because they're more expensive to foreigners.

So the tariff and the exchange rate cause imports to move in different directions, but importantly, they both cause U.S. exports to move in the same direction—a decline. Miran clearly knows this and understands it, so he reaches outside of the international trade theory to fix this problem.

"Policymakers can in part alleviate any drag on exports by an aggressive deregulatory agenda, which helps make U.S. production more competitive."

Basically Miran is saying that U.S. exports will certainly go down as a consequence of the tariffs, but the U.S. can offset this with other policies like deregulation. But if deregulation is a good idea, it's a good idea regardless of the existence of tariffs. We shouldn't deregulate more only because we're hamstringing our trade relations, we should deregulate more because it's good in and of itself. Deregulation should not be tied to our trade policy, it should be pursued on its own merits.

Once you remove that external solution to a problem his tariff policy causes, then it's clear that one of the costs of the trade barriers is Americans exporting less, and trade deficits will not fall as much as Miran and Trump want. It's an open question what the end effect would be once all the dust settles.

Footnotes

1As an interesting aside, this is a natural outcome of taking the world off the gold standard, and making the U.S. dollar the primary medium of exchange around the world. If some percentage of American dollars are used as a global currency, that means that money won't be used to buy American goods, and American trade deficits will be higher.

2Another side note, he refers to the Cavallo paper which found that much of the cost of the tariffs on China in Trump's first term weren't passed through to consumers, which he uses to support his conclusion, but the reason that that happened, as explained in the paper is that the U.S. importing companies believed they'd be temporary so they ate the cost and didn't pass them on to consumers. American producers still felt the pain, not China. It wasn't because currency rates adjusted perfectly to offset, it was because American corporations absorbed them instead of consumers.

3These percentages aren't going to be exact but are rounded off for explanatory purposes. Using exact percentages doesn't affect the general argument.