"We find that tariffs passed-through almost fully to US import prices, implying that much of the tariffs’ incidence rests with the United States."

--Authors of paper cited for tariff calculations.

On Wednesday, Trump announced his new tariff rates. They were higher than anyone was expecting and higher than he campaigned on.

Part of the reason they were higher than expected is because Trump frequently argued he would be imposing "reciprocal" tariffs, and everyone interpreted that according to the plain meaning--that he would set tariffs on other countries at the same rate they set on our goods. The tariffs he announced were not that.

It didn't take long for enterprising citizens to crack the formula used to determine them, and instead of being reciprocal, they were set based on the trade imbalances between the two countries, not the tariffs. Specifically, they were one half of the trade deficit divided by the imports. To my knowledge, this is not a value economists or policy makers use or even have a name for.

It's become the default position that the tariff rates are nonsensical and should be dismissed with prejudice, but in my view, the approach described by the trade representative isn't without some merit, even if it was applied incorrectly and probably just a post-hoc rationalization.

What the Tariff Rates Were Intended to Do

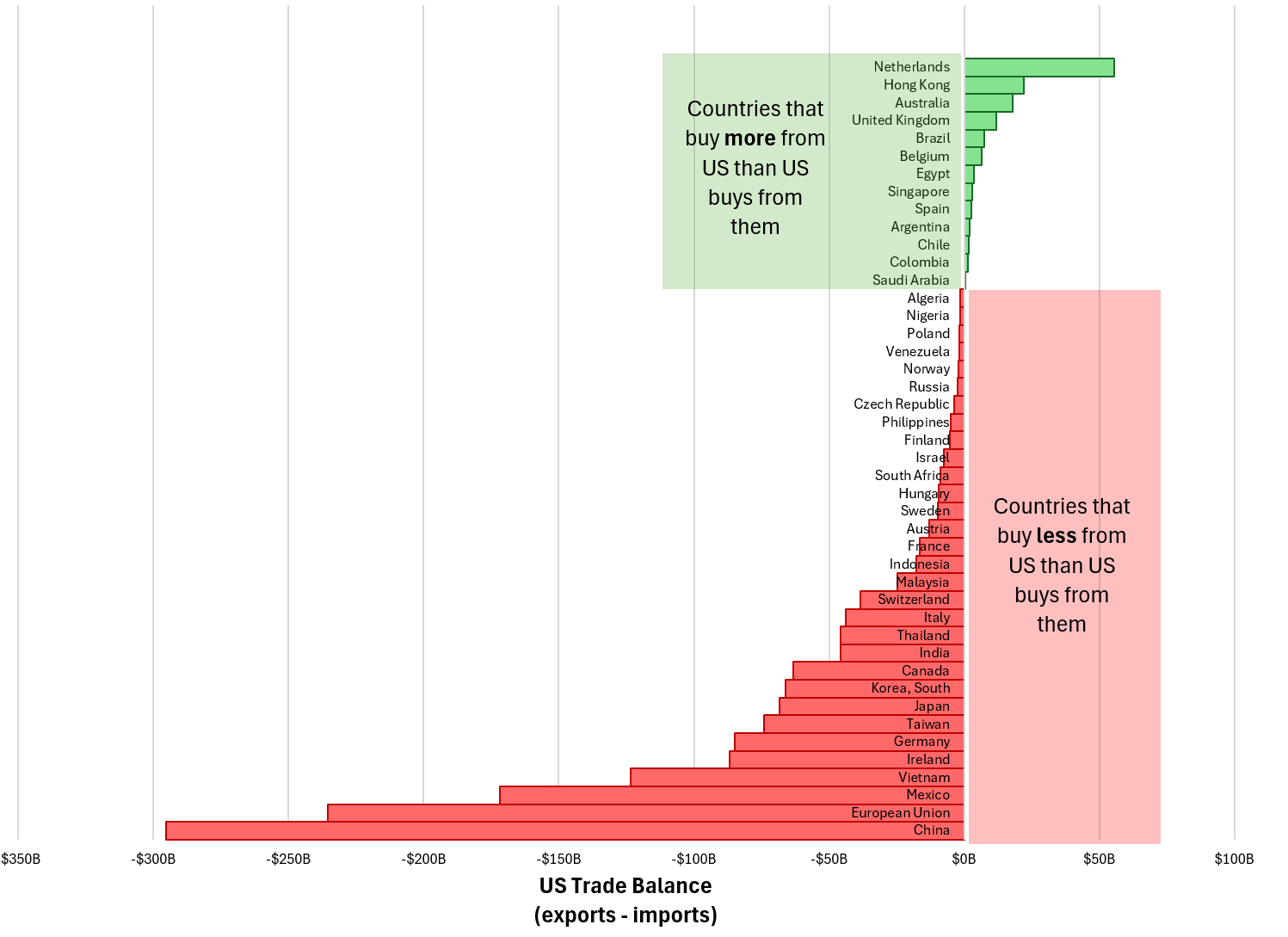

The Trump administration's story is that practically every country in the world exports more to the US than they buy from us, and that this imbalance is caused by a suite of trade barriers including tariffs. To reciprocate, Trump only has authority to modify tariff rates, so he'll exclusively use the tariff rates to counteract all the trade barriers from other countries.

In other words, he sees (or rationalizes) the trade deficit as a measure of the unfairness of other countries' trade restrictions, and is working to reduce that imbalance. Specifically, he wants to reduce it by half for each country.

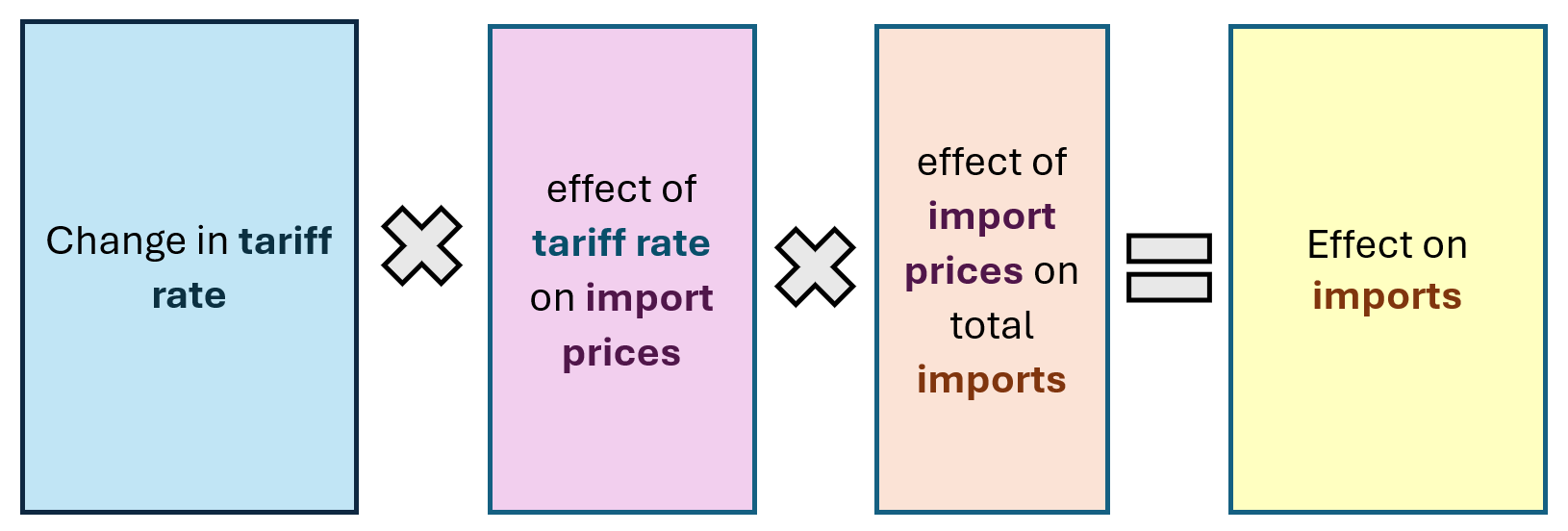

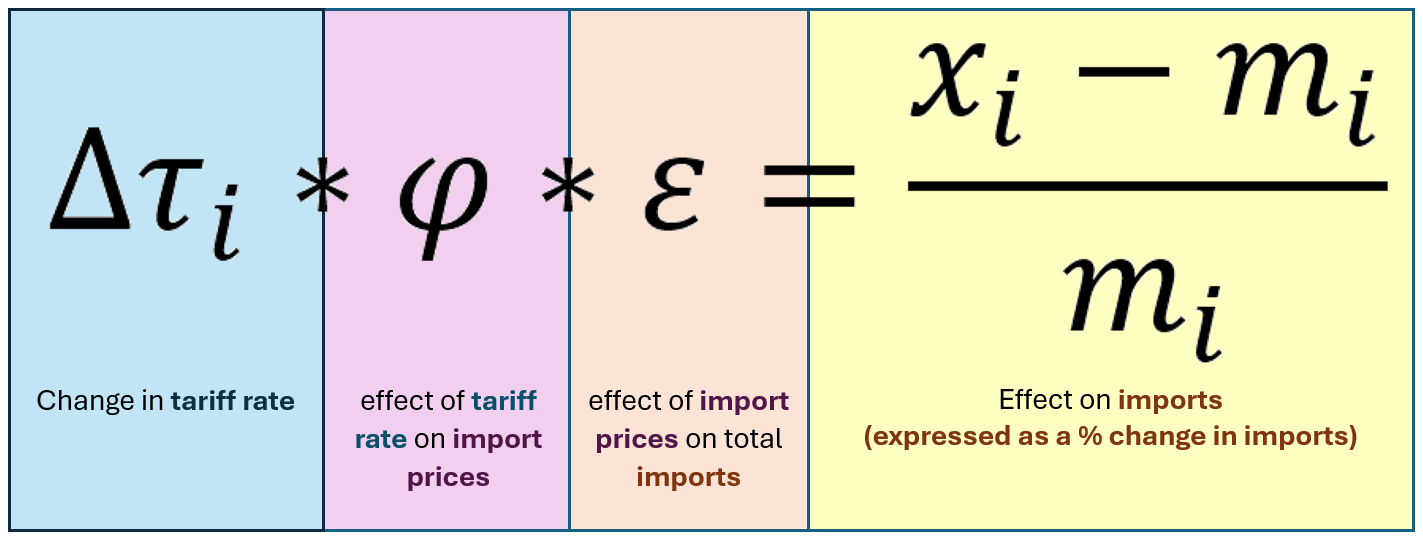

To accomplish this, he's relying on a basic, over-simplified economic relationship. Abstractly, the administration is saying "Ok, we want to reduce imports by X, so what tariff rate will accomplish that? If we assume a tariff increases the price so much, and the price reduces imports by so much, then we can determine what tariff to set to meet our targets."

This is the basic approach they're taking, and the formula that they provided in their announcement, which they claim is how they determined the tariff rates matches it, you just have to re-arrange some of the terms, like one might in Algebra.

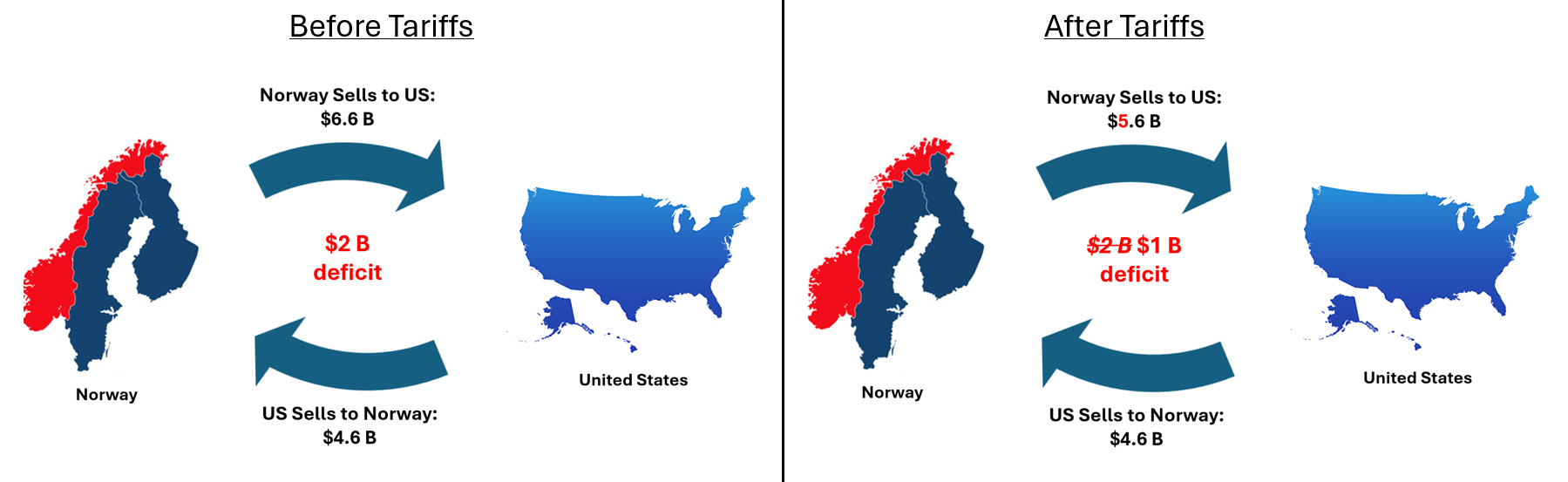

Lastly, to determine the new tariff, they start by calculating the trade deficit (export - imports), then divide that by the total imports to get the percentage change in imports. Then they divide by the psi and eta to get to the new tariff. Using the numbers for Norway, as in the diagram above, this would be 6.6 billion in US imports from Norway - 4.6 billion in US exports to Norway leads to a deficit of 2 billion. Cutting that in half would mean reducing the 4.6 billion in exports by 21.7%1.

In practice, when they ran their numbers, the effects signified by epsilon and psi cancelled each other out because one was 4 and the other was 1/4.

What They Got Wrong

What They Got Wrong - Big Picture

In applying this, they made several mistakes. The first and largest one is that this is a vast over-simplification of how the world works. For the effects of tariffs on prices and the effects of prices on imports, they're using one, global value for each. This is immensely unrealistic. These effects are going to vary for every country, for every product, and over time as the conditions under which the global economy operates change. Economists have attempted to estimate them at different times using different approaches and have come up with an array of numbers. Assuming there's only one belies reality and will produce incorrect results.

It also fails to account for economic and political reactions. A higher tariff will typically reduce imports, but it will also shift production from one good to another or from goods to services or from one country to another and so on. A single formula using a constant effect will not account for this.

They also committed several underlying mistakes in logic. First, there's no reason that we should even try to balance the trade. It will not make us better off; it will, in fact, make us worse off.

Second, there's no way that reducing imports by a set amount is going to have the desired impact on the trade deficit. The world is much more complicated than that; it's like squeezing a balloon. Increasing tariffs will certainly cause some rearrangement, but the underlying incentives that create the imbalances will remain in place. Imports may fall, but that means there'll be less American money sloshing around the world, meaning less money to buy our goods, less money to buy our services, less money to invest in US companies. The new state of the world will look more like the current state than the state Trump envisions.

The new state of the world will look more like the current state than the state Trump envisions.

What They Got Wrong - Weeds

The equation they use only works if the effects they apply match the equation. For example, if one of the effects they use is determined by calculating the percentage change in imports based on a percentage change in tariffs, you can't just plug in the overall tariff rate and get the right answer.

You must plug in, specifically, the percentage change in tariffs. It's like converting centimeters to inches. There are 2.54 centimeters in an inch, so to convert 6 inches to centimeters, you have to multiply 6 by 2.54. If you substitute 6" for the equivalent length in feet by 2.54, you'll produce gibberish.

The values they're using aren't compatible with each other. The "effect of import prices on total imports" argument is an elasticity, which means the percentage change in price generates a percentage change in imports. But the rest of the equation produces a percentage point change in prices.

As AEI has also pointed out, they're also misinterpreting the effects they are using. Most importantly, they're using 0.25 for the effect of tariff rate on import prices, but the paper they're pulling that from estimates that as the effect on retail prices that consumers ultimately see, not the prices that the corporations that imported those goods experienced.

This is an important distinction, because the paper was reviewing a much narrower tariff on one country for a small set of goods, and these could have been considered temporary. They found that the tariffs did affect the prices that the importing companies paid, but these companies absorbed them themselves (with reduced profits), and didn't pass them onto consumers. In the long-run, though, they would certainly be passed on to consumers.

AEI calculates what those rates should be using a more appropriate value here, and I generally agree with what they find. I would note, however, that the other effect they use--the import/price demand elasticity--was set at a higher rate than appropriate, too. If you use prevailing effects for both values, the tariff rates would be about half of what Trump announced, not one-fourth, as AEI determined.

Data Sources

Current Tariff Rates - NY Times

Current trade levels - Census

Other bilateral trade info - WTO

Footnotes

1These numbers are meant for illustration only. They are not the same numbers Trump used, so will produce tariff rates different from Trump's.