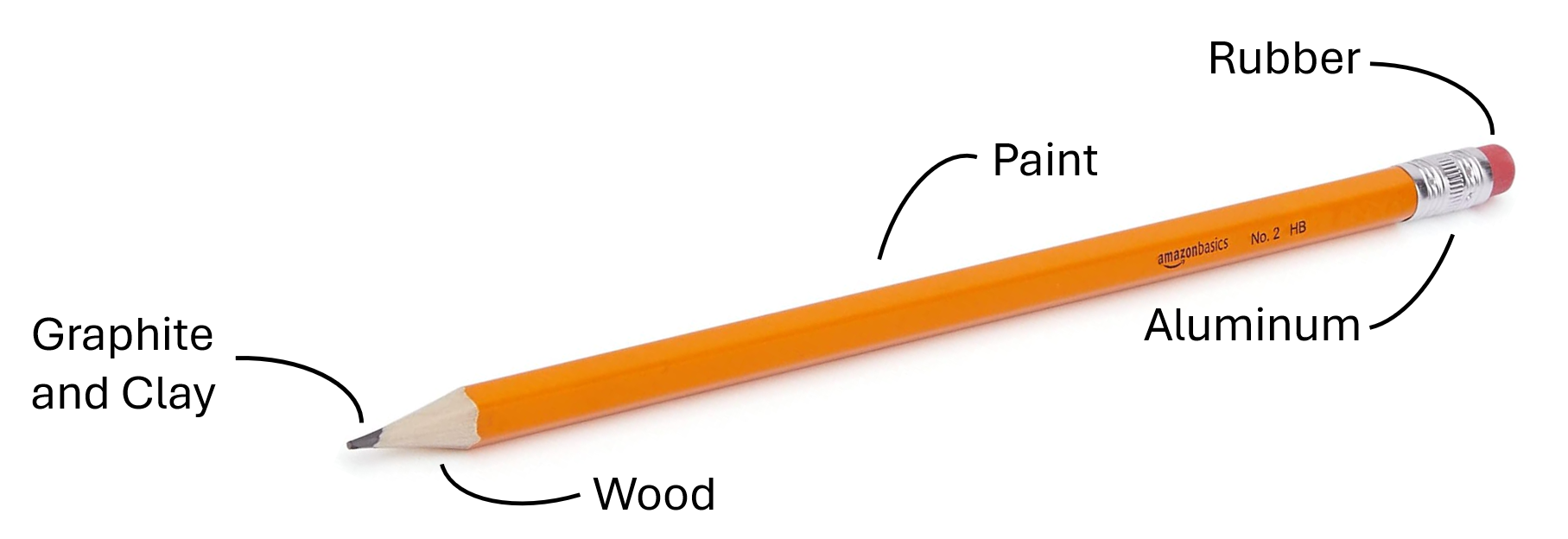

The video of Milton Friedman's "I, Pencil" monologue has been en vogue the last couple weeks due to the recent elevation of international trade into the vibegeist. The underlying message of "I, Pencil" is that no one person could possibly manufacture even something as simple as a pencil.

While it has a quite limited set of components—graphite, wood, paint, aluminum, and rubber—each of those components requires its own ecosystem of people, goods, services, and expertise to produce.

Trade is what makes pencils so ubiquitous we can buy them for pennies within minutes and is also what allows for a variety and quality that would be impossible without it.

The pencil and its components, however, illustrate another crucial lesson about trade, one that I tried to describe in my previous post "Trade Makes Us Rich Beyond Measure." Namely, that while "I, Pencil" explains how no single person contains the knowledge or skills to recreate a basic pencil, it's also true that trade opens up a world of components and expertise that are not available in one country. Trade is what makes pencils so ubiquitous we can buy them for pennies within minutes. It also makes them better quality and more diverse than they'd otherwise be. Finally, it allows us to divert our highly skilled, highly productive workforce to more valuable products like nuclear reactors, gas turbines, or spacecraft.

A Global Grocery Store That Sells Everything

While the "I, Pencil" message is that the pencil is not nearly as simple as it seems, a pencil, on its own, comprises just a handful of components: graphite, clay (mixed into the graphite), wood, paint, aluminum, and rubber. Imagine you've been tasked with producing a pencil from scratch, and you have to source these materials. Because of international trade, you have more options than you can possibly research individually.

You can purchase graphite from as nearby as Canada and Mexico or as far away as Madagascar and Mozambique. You can even choose to support Ukraine via purchases of graphite.

The wood in a pencil is typically cedar. The United States is one of the top producers of cedar in the world, so you can get that domestically, but if you would prefer to denude another country's forests, you can go just across the border to Canada or any of a number of countries in South America, Africa, or Asia.

Top 10 Timber-Producing Countries

Forty countries produce more than 1,000 metric tons of aluminum. Countries that span South America, Africa, Asia, and Europe. From the southernmost tip of the inhabited world to the northernmost and in every time zone, there's a country that produces aluminum. The availability of this key metal reflects both industrial capacity and access to the raw ore that is used to produce it.

Aluminum-Producing Countries

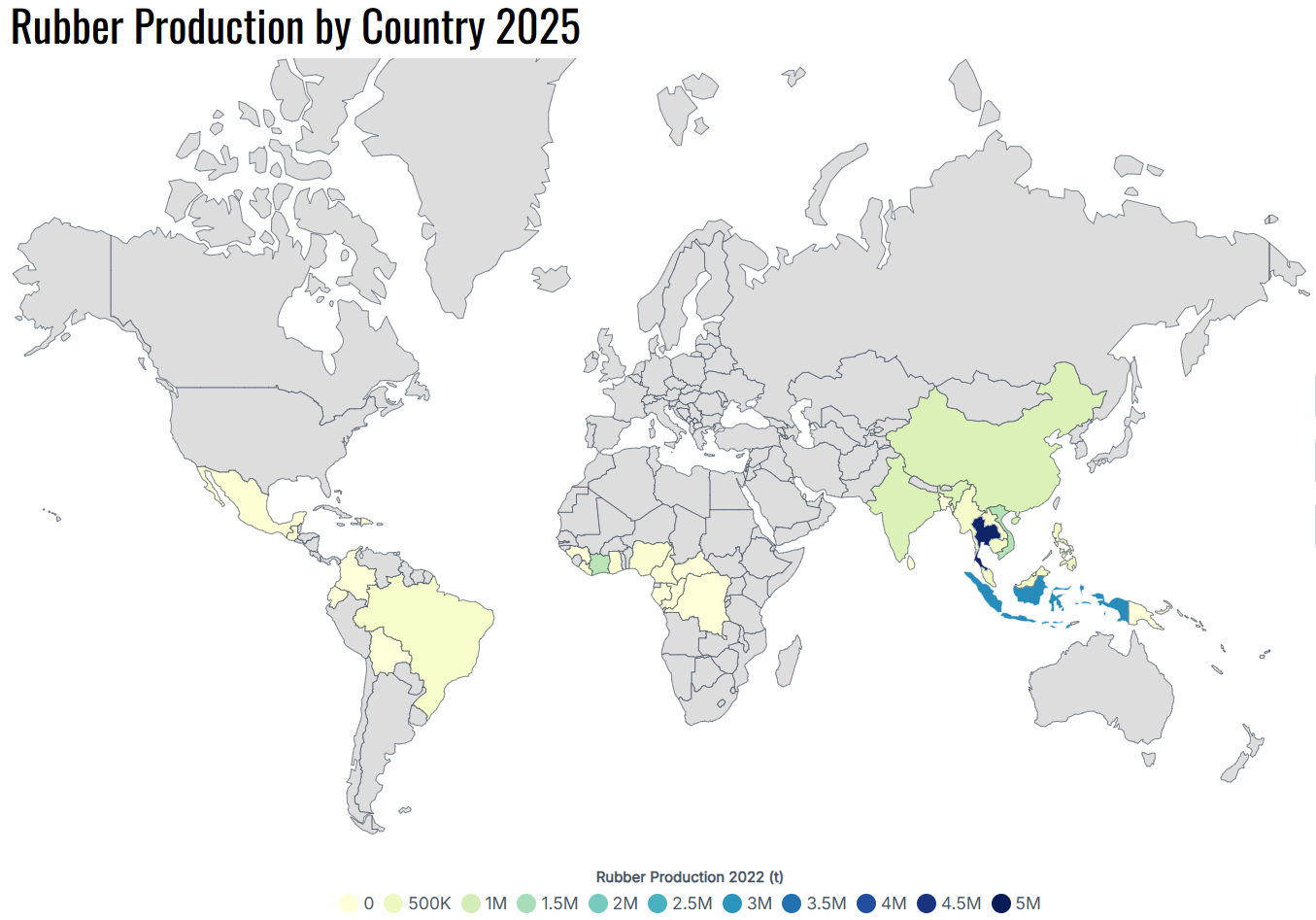

Rubber production is more concentrated around the equator, yet there are still three countries in North America, four in South America, ten in Africa, and practically all of Southeast Asia.

For each of these pencil components, you can choose among the countries that produce them, yet also among individual suppliers within those countries. Just like when you're shopping for household items, you can choose based on price of the component, its quality, quantity available, proximity (to manage shipping costs), or even because of a country's politics.

The world is your grocery store, and all of these countries are competing with each other to get you to buy their product based on the factors I listed above. This competition, again like the grocery store, drives down prices and drives up quality and variety.

Ubiquitous Variety

We are swimming in cheap pencils

On Amazon, you can buy 30 pencils for $0.15 each—that's one dime and one nickel. Some people argue that there's a loser and a winner in every exchange, but that is wrong. Both sides are winners. When you buy a pencil, you're giving up a couple of coins and obtaining something that you will use so infrequently, it's more likely that you end up throwing it away than wearing it out. Whoever produced the pencil has even less use for it, and makes money when you buy it. You are both winners. Such is it with every item you purchase.

The pencil choices are innumerable

Not only are pencils cheap, but their variety is bewildering. Jumbo pencils, pencils painted red, and colored pencils.

At Dick Blick, they walk you through how to navigate the dizzying array of pencil options available. You can choose your graphite grade, of which there are at least 24 available on that page and your wood type, of which there are three. Also the shape and diameter of the pencils are options. Just on that one page, I count at least 200 different combinations of options that are available for sale, and it doesn't even include colored pencils.

We Shouldn't Make Pencils in the U.S.

It would be an enormous waste.

The deluge of pencils is only possible because of trade. Having the other 7.7 billion people in the world mining graphite and aluminum ore, mixing paint, harvesting rubber, and producing aluminum, and even producing the pencils abroad and selling them to us enables the variety and cheapness we enjoy. Few people think about this, but one of the reasons the U.S. does not produce graphite is that however much graphite may be available in the United States, its quantities are small and its access is extremely limited, especially when compared to other countries.

Pencils are as cheap as they are because sourcing the materials from countries that have the components in abundance, those components are markedly cheaper than if the U.S. tried to mine graphite domestically. It cannot be emphasized enough that this is a gain. This is a gain for everyone. Because graphite is cheaper elsewhere, Americans benefit, and so do the producers.

This applies to manufactured goods as well naturally occurring ones. The U.S. could surely produce its own aluminum, but consider the costs, not just the cost of building the factories but the loss of economies of scale. The more of a product that one plant produces, in general, the less costly it is to produce on average. It's cheaper to build one large factory with one set of logistics like electricity, HVAC, assembly process, etc., than ten small factories where you'll be needlessly replicating the factory's systems. Also, the employees you hire will be more specialized and more knowledgeable. Ten factories will require ten sets of employees that can do the basics and won't be as specialized or productive as one larger factory, which will enable that factory to produce more pencils, more cheaply than the total across ten factories.

All of these factors add up to one truth of trade—it enables a level of prosperity and abundance beyond what any country can accomplish by itself.

All of these factors add up to one truth of trade—it enables a level of prosperity and abundance beyond what any country can accomplish by itself. This is not because the United States is inferior to other countries in its resources or in its people, but because its resources and its people are limited in number. Even the most productive people in the world only have so much time in a day, and their productivity is enhanced by relying on others to take care of the basics. So it is with a country.

This concept is also demonstrated in this video of a guy making his own sandwich from beginning to end, from scratch. Growing and pickling cucumbers, harvesting wheat, and churning butter to bake bread. Of course, a person can do these things, but they take up so much time and energy, all for a pretty average sandwich. By applying time and energy to one thing, and one thing you're good at and other people value, you can trade your productivity for so much money that you can buy more and better sandwiches made by more experienced and focused people. So it is with a country.

Shifting production from abroad to the U.S., as some politicians want, will mean shifting our unparalleled workforce from high-value goods and services to lower-value goods and services, being less productive and consequently, less wealthy.

Instead of pencils and the other goods we import, our highly productive and knowledgeable workforce can focus on much more sophisticated and valuable goods—industrial turbines, jet engines, nuclear reactors, and more. Shifting production from abroad to the U.S., as some politicians want, will mean shifting our highly focused workforce from high-value goods and services to lower value goods and services, being less productive and consequently, less wealthy.

Conclusion

It isn't obvious, but trade does make us richer. It makes us richer by letting us focus on our strengths and asking others to supply our weaknesses (their strengths). The wealth it creates is immeasurable and we should think carefully about whether the lives we've become accustomed to would still be there in a world without it.