Main Takeaways

- Government projections for new policies consistently underestimate costs and overestimate benefits

- Details here for three such misses

- The media and the electorate should both exercise much more skepticism and scrutiny of these numbers when considering proposals from administrations and agencies.

On January 5th, the FTC announced that it will implement and enforce a rule that will prohibit non-compete clauses in labor contracts, nation-wide, retroactively, and proactively. To support their new regulation, the FTC claims that nationwide, earnings will increase by up to $300B. Informed citizens should be well to remember that, while the FTC is basing their estimates on what they consider the best possible evidence, it is often the case that the government projections turn out to be faulty, either because the research was too thin to properly predict the effects, because the research was just flat incorrect due to the bias of researchers, or because unforeseen circumstances undermined the basis upon which the research was conducted. A good example of the last possibility is projections on Medicaid enrollment for the ACA. I do not fault analysts for underestimating how politicized the ACA would be and that right-leaning states would eschew Medicaid expansion, the Obama administration would threaten to take away all of their current Medicaid funding, or how the Supreme Court would fall. Consequently, I don't fault them for over-estimating the number of people insured through Medicaid.

Another possibility is that once a policy is enacted, particularly those that redistribute benefits to groups, it often is expanded either in the number of people eligible or the amounts provided. This has been the case with the ACA and also student loan forgiveness. In this case, the analyst's job is not to predict how the policies will change, but to predict the effect of the proposed policy directly. It should be left to think tanks and pundits to extrapolate potential effects the political world may have.

Still it is worthwhile to consider some of the policies enacted, the effects they were supposed to have, and the effects they actually had.

Electronic Logging Devices for Truckers

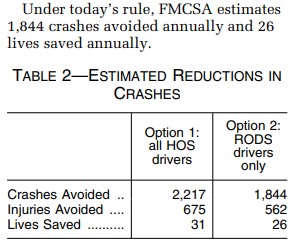

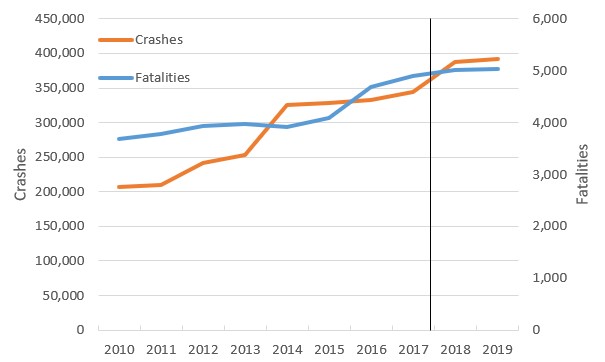

In late 2015, the Department of Transportation's Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration proposed a rule that would require truckers to use electronic logging devices to track their hours driving. The idea behind it was that truckers were driving more than they were able to, and becoming tired and more dangerous. Electronic logging would force them to limit their driving and thereby increase the safety of them and other drivers. In its original regulation, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration claimed that EDS would save 26 lives and prevent 1,844 crashes per year, but in the two years after implementation, and before Covid, both fatalities and the number of crashes increased. The explanation is that when truckers are time-constrained, it causes them to drive faster to make up for the time they won't be on road, undoing any benefits of the reduced time. The Department of Transportation also didn't account for the price increases it caused.

Coverage of the 2017 protest to block

Nationalization of the Student Loan Industry

In 2010, President Obama signed a law that effectively nationalized the student loan industry, preventing any guaranteed loans from being offered by private banks, only from the government. The government estimates it will save $61 billion over 10 years. In fact, by 2022, the government had cost the government and taxpayers nearly $200 billion. Plus the costs of the debt forgiveness package Axios estimated to be $300 billion. GAO report on the student loan program in 2022"A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report released in July found the Department of Education predicted that student loans would generate $114 billion for the federal government; they instead lost $197 billion — a $311 billion error, mostly due to incorrect analysis." --Foundation for Economic Education

There are certainly benefits to subsidizing student loans, as a well-educated workforce will enhance the economy for everyone, but taxpayers deserve to have an accurate expectation of those costs and benefits to decide. And if time shows that that analysis was off, they should have the chance to reconsider.

ACA

In 2019, the average monthly premium per enrollee in the individual market was $515, up from $217 in 2011.

The three examples above illustrate that the analysis the government conducts and propogates through the media to support its regulations is all too often incorrect and underestimates costs and overestimates benefits. The media and the electorate should both exercise much more skepticism and scrutiny of these numbers when considering new proposals such as the ban on non-competes or environmental regulations.