The FTC is currently considering a blanket ban on non-competes. While the FTC claims that the comprehensive ban will increase wages across the economy, physicians are one of the few professions called out specifically, because non-competes are more common for physicians than for many other professions.1

The purpose of non-competes is more apparent for physicians, particularly in group practices. Like some other service industries, individual healthcare works best when the patient and the doctor develop a long-term relationship so that the doctor has better knowledge of the patient's history and panoply of health issues. This makes diagnosing new problems or anticipating future problems more likely.

Due to this long-term nature, group practices are especially concerned about losing a physician and all the patients who might want to remain with him. There may also be some degree of information that the physician could use effectively to compete were he to strike out on his own.

It is unsurprising that employers, then, want to take steps to make it difficult for their employees to break away and start competing with them. Hence, they have newly hired physicians sign non-competes that will create an area within which their employees cannot practice medicine. The physician can often still start his own practice, but it will need be a certain distance away, which should stifle any patient uprooting.

The American Medical Association's views on non-competes are explained in a submission to the FTC's January of 2020 workshop on non-competes. They lay out the advantages to the employers and employees but also discuss several drawbacks. To balance out these competing interests, they support the use of non-competes but with limits.

This is altogether different from how the FTC mainly talks about non-competes, in terms of minimum wage workers and tech workers who have skills that they intend to transfer to another employer. Certainly some tech workers want to create their own company and some physicians want to work for another practice or hospital, but these circumstances are materially different and be treated separately despite how FTC lumps everything into one category.

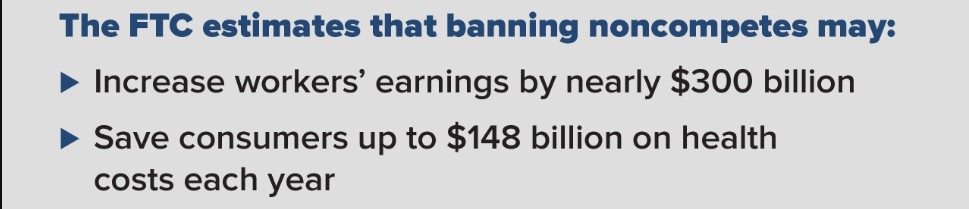

In the FTC's infographic, they claim that banning non-competes will increase workers' wages by $300 billion dollars and save consumers $148 billion on health costs.

If you're like me, you wonder how banning non-competes can save consumers money and increase the pay of physicians. Presumably, if physicians are being paid more, then the costs of providing healthcare will increase, and consumers will see higher prices. Somehow, the FTC claims that banning non-competes will produce benefits on both sides of the ledger.2 How can this be?

Firstly, the estimate of wages, is an average across all professions, all skill-levels, regardless of whether they have a non-compete, so it's not entirely clear from their fact sheets and infographic if some professions will see a lower wage while others see a higher wage, but it averages out to a higher wage across the economy. If that is the case, they certainly don't highlight it.

Non-Competes Don't Raise Physician Salaries?

Digging into their supporting documents, though, it becomes apparent that they are claiming that no professions will see a wage decrease, even physicians. Surprisingly, this is despite the claims of the paper they cite. "Finally, Lavetti et al. find that use of non-compete clauses among physicians is associated with [14% higher earnings] and greater earnings growth."3

The FTC discounts this because it is merely an "association". In other words, it was not an experiment designed to suss out causal factors, but an observation that areas with high physician wages also tend to have more usage of non-competes. Therefore it's impossible to know if proscribing enforcement of non-competes would cause wages to decrease.

The FTC then admits that the study in question tried to address this issue by comparing wages in high-enforcement states against low enforcement states. It doesn't include the result from the study but does make sure to say that the results can't be trusted because it was only two states.4 Notice a pattern of very high thresholds of evidence to demonstrate an effect counter to what they're claiming?

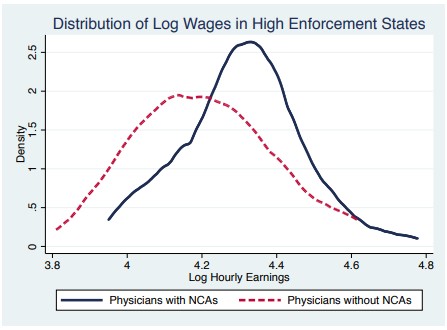

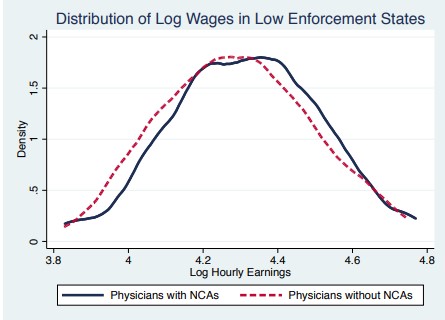

Granted, the study doesn't seem to provide a number for the effect, but it does still show a positive correlation of physician wages with enforcement of non-competes, contrary to FTC conclusions. However, they do provide this graphical portrayal of how wages differ between physicians with non-competes and those with non-competes in California (low enforcement state) and Illinois (high enforcement state). Taken together, they seem highly suggestive that the non-competes are responsible for the wage difference.

In effect, the FTC is saying that this study that compares wages for physicians with and with non-competes, and also accounts for enforceability still is a worse predictor of wage effects for physicians than two studies done before states relaxed enforcement of non-competes and were not experimental in nature.

Non-Competes Raise Healthcare Prices?

So that's how the FTC handles the wage issue, what about the health care costs? How does it determine how much money will be saved consumers? For that, they turn to another paper.5 This paper finds that enforcement of non-competes, leads to organizational changes in physician practices, which increase concentration, and then increase prices.

The FTC points out that the authors considered the possibility that the physicians increase their earnings, but they assure us that this isn't the case because the largest price effects are present in procedures that are the most equipment-intensive, and the smallest price effects are present in procedures that are the most labor intensive, as determined through Medicare RVUs.

Notably, this is an extremely complicated way to determine this, and the more steps, the more potential errors are introduced both in interpretation and missing important relationships. They did not simply look at the salaries of physicians across the practices, or if they did, they didn't report it, but applied their approach to estimated values of a Medicare-created metric of value and drew a conclusion.

This is not to say they're wrong, just that it is so convoluted it makes drawing conclusions more difficult than they say. In reality, all that they can say is that the price effect is more pronounced for equipment intensive procedures. If physicians are paid an annual salary, and are not paid for individual procedures, I believe that their conclusion is no longer valid. In fact, they even say that "effects of Non-Compete Agreements on prices appear to occur through a mechanism related to practice organization and overhead costs, rather than through one related to physician labor costs."

It would seem to me that if physicians are paid a salary by their practice, and not procedure-specific fees, then that would qualify as overhead costs. Indeed, their entire theoretical mechanism seems to be non-competes lead to less competitive physician markets (presumably because they stifle formation of competing practices), and they use their bargaining power to extract higher prices from insurance companies.

The FTC claims, from this, that they then don't use that money to bolster their own salaries, and don't say what they then do with it, but this somehow also leads the physicians to have lower salaries. I suppose this could be possible if there was some owner/administrator that didn't care about physicians who forced them to sign non-competes, then got higher reimbursements from insurers, and kept all the money for themselves.

Notably, the paper that the FTC cites, doesn't itself say that physician salaries are harmed by non-competes, only that it's not physician salaries that cause the increased prices. In fact, it implies the opposite. "[Non-compete agreements] increase average costs because physicians must be compensated for accepting [one]." (Emphasis added)

So, it remains unexplained by FTC how consumers are going to have another $148 billion while also physicians are going to be paid more. How both providers and purchasers are going to end up with more money while no one will be worse off will be an impressive feat if the FTC can pull it off.

Prices and NCAs

The FTC provides no further evidence linking prices and NCAs in any industry, except for the one paper on physicians. It stands to reason, though, that if salaries are going to increase, then the costs of labor for these firms will also increase. And when costs increase, prices go up. To neutralize this argument, they claim there are no studies that show this, and then suggest alternative possibilities that would preclude it.

They cite one paper that suggests costs do not impact prices in goods manufacturing. Of course, this is a single example at a single period of time and only talks about the degree to which pass-through takes place, not that it says it doesn't exist. It also defies logic, economic theory, an enormous amount of experience, and also the FTC itself.

After mentioning that paper, they rest their case on the suggestion of possible countervailing forces that keep prices down: NCAs increase concentration, NCAs reduce innovation, NCAs worsen worker-firm matching. While all of these are true to a degree, they're relying entirely on the idea of them and assuming that the effects are going to be greater than the more direct effects on prices of raising the costs of labor without providing a single bit of evidence to support this assumption.

Footnotes

1Lavetti et al (2020) estimate that 45% of physicians worked under a non-compete clause in 2007.

2This primer provides a review of all the information I could find on the FTC's non-compete case.

3FTC Non-Competes Background Document. p. 23

4For what it's worth, I don't think this accusation is true. There is a graphical representation of results that is just comparing Illinois to California, but the model results included all of the states surveyed, as best I can tell.

5Naomi Hausman & Kurt Lavetti, Physician Practice Organization and Negotiated Prices: Evidence

from State Law Changes, 13 Am. Econ. J. Applied Econ. 258, 284 (2021).